Americans Starting Businesses at a Record Pace, but Are They Good?

The number of business owners applying for employer identification numbers in 2020 surpassed the previous year’s total by mid-October.

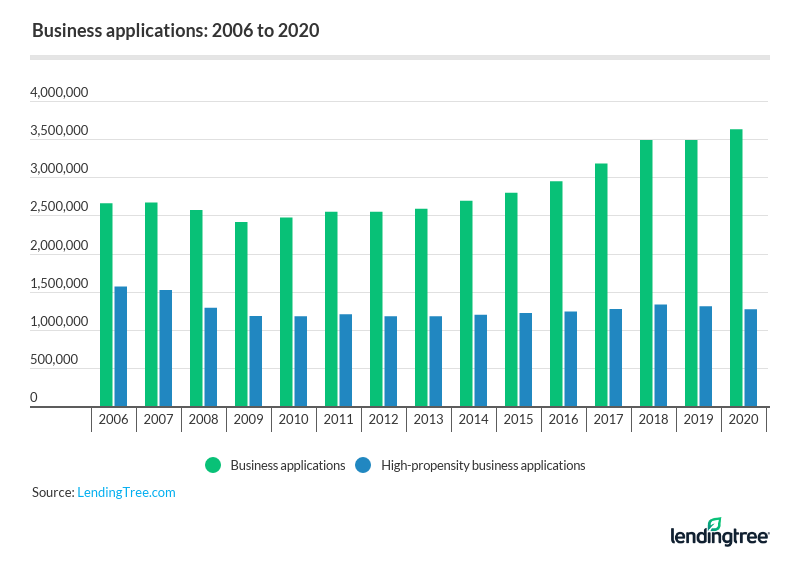

But data on high-propensity business applications — meaning a higher likelihood of the businesses having employees — suggests many of these new businesses may be empty calories when it comes to the economy. In fact, only 35% of 2020 business applications through mid-October were from high-propensity businesses.

LendingTree researchers analyzed the latest Census Bureau data on business applications to determine the impact of these new businesses on America’s entrepreneurship boom.

Key findings

- 59% of business applications in 2006 — the first year for which data is available — were from high-propensity businesses, but that figure has dropped by 41% to 35% through mid-October.

- Business applications in 2018 — the year the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act went into effect — grew by 10% year over year, compared with 8% in 2017. But in those years, high-propensity business applications grew by just 5% and 3% year over year, respectively.

- 2020 saw a large spike in business applications after the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act was signed into law on March 27. In the first 13 weeks of the year, an average of nearly 74,000 businesses applied for employer identification numbers (EINs) weekly. From the following week through mid-October — the latest available data — the average was nearly 89,000.

- The percentage of business applications deemed high-propensity has fallen in all 50 states, plus the District of Columbia, since 2006.

Tax incentives encourage Americans to start businesses

From 2006 to 2013, there were about 2.5 million business applications a year in the U.S. Starting in 2014, the number of businesses applying for EINs grew year over year, in step with an improving employment situation across the country. At the same time, though, the percentage of business applications deemed high-propensity has dropped every year since 2006, despite six yearly increases in the number during that period.

Check out our guide to getting a startup business loan.

There was an especially large spike in business applications when the Tax Cut and Jobs Act went into effect in 2018, which made operating a business more tax-friendly.

But despite the extra benefits to starting businesses, the enthusiasm did stall in 2019. After the 10% growth in business applications the previous year, the number of business applications fell, though by only 330. Along with the drop in overall business applications, the high-propensity rate also fell just over half a percentage point.

Relevant to the growth of business applications is a newer provision that allows a deduction of up to 20% of qualified business income for owners of certain businesses. This creates an incentive for people to set up new businesses to monetize side hustles, but also — in theory — encourages people to set up pass-through entities to maximize their after-tax income.

As such, business applications in 2020 — despite the worst economy since the Great Depression — have already surpassed the 2019 total. The speed and urgency to get money out to small businesses encouraged many of them to take advantage of Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loans through the CARES Act. But businesses needed to be careful, as there were instances of alleged fraud.

Many people may be starting businesses thanks to newer tax incentives. The tax code is complicated, though, and you’ll want to make sure you or someone you work with is able to make sure your business is making the most of the available tax incentives.

Business applications from e-commerce shops grow by 4 times

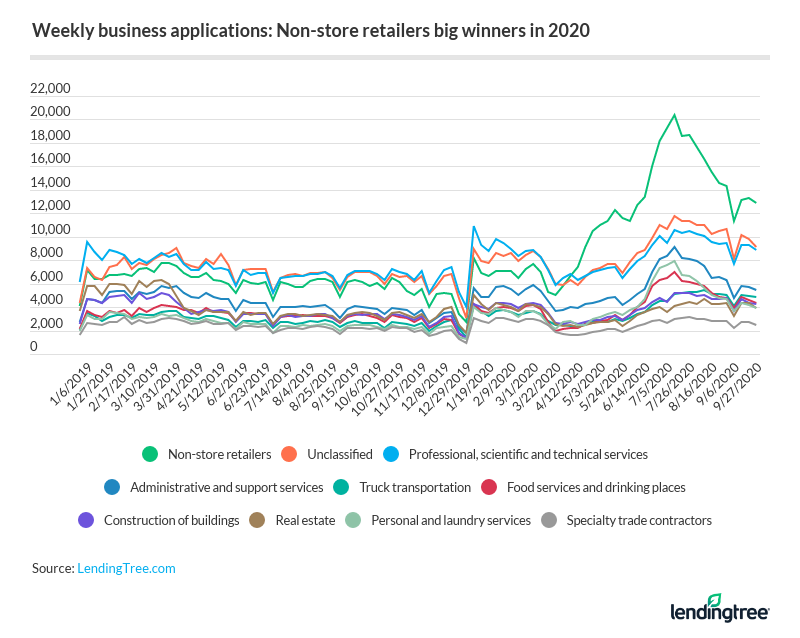

For people starting businesses in 2020, the go-to option was non-store retailers, or e-commerce shops. Non-store retail covers electronic shopping, mail-order houses and direct selling establishments (more on this soon), which can often use multilevel marketing models.

Between the week of March 22 — when the CARES Act was signed into law — and the week of July 12 — when CARES Act money was being paid out via PPP loans and supplemental unemployment insurance — the number of weekly business applications for non-store retailers grew by four times, from 5,070 to 20,370. July 12 was the peak for business applications for non-store retailers. In the following 10 weeks, business applications fell to an average of about 15,400 weekly.

Between the week of Dec. 29, 2019, and the week of March 15, 2020 — the last prior to the CARES Act being passed — there were an average of about 6,600 applications for non-store retail businesses. After that, from March 22, 2020, to Oct. 3, 2020 — the latest available data by industry type — there was an average of nearly 13,200 non-store retail business applications per week.

Non-store retail is the type of business you might open up to take advantage of a side hustle, so it makes sense that as the COVID-19 crisis ripped through the country, more people were spending time thinking of ways to make some money.

Another potential explanation for the rise in e-commerce businesses might be the additional $600 weekly in unemployment insurance. That money flowing to unemployed people led to a personal savings rate of nearly 34% in April, the highest on record, and may have given some people the financial breathing space they needed to set up a business.

Number of direct sellers up 28% since 2016

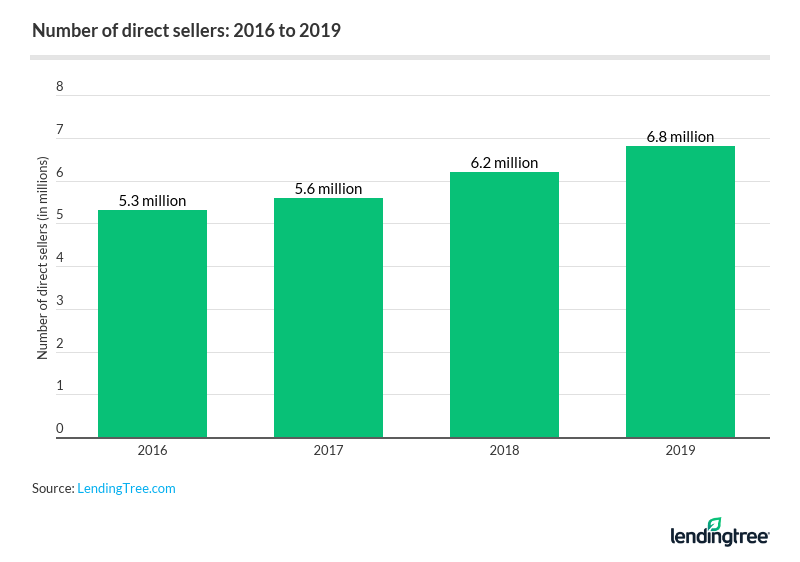

Another trend that aligns with the growth in new businesses is that of the direct seller. Recent media reports have highlighted the plight of people involved in direct-selling businesses, with a particular focus on women’s clothing company LuLaRoe.

The number of direct sellers grew from 5.3 million in 2016 to 6.8 million in 2019, according to data from the Direct Sellers Association — an increase of 28%.

These are the types of businesses that one might think the IRS wouldn’t categorize as high-propensity, because of their low likelihood of leading to employees.

How likely are direct sellers to apply for a business EIN? An analysis of New York and California business records suggests that they do, at least for LuLaRoe businesses. However, we can’t speak on this certainty, as the U.S. Census Bureau doesn’t track high-propensity business applications by industry type.

Wyoming leads the way in business application growth

Not every state has seen the same level of dramatic business application growth. In Wyoming, for example, average annual business applications grew by 193% from 2006 to 2019. In 2006, the state had 6,200 business applications, but that figure rose to nearly 18,200 in 2019 — and that growth has continued.

2020 business applications in Wyoming have already surpassed 2019 levels. The perceived quality of those businesses is also down over that period, though. In 2006, 62% of business applications were made by high-propensity businesses, compared with just 31% through mid-October 2020.

Despite remarkable growth in business applications across the country, business in some states is not quite booming. In Nevada, annual business applications are down 4% between 2006 and 2019, and high-propensity business applications continue to fall, too. In 2006, 60% of businesses were high-propensity, but by mid-October 2020, that figure was 33%.

4 tips for starting a successful business

We asked Melissa Wylie, senior small business writer at LendingTree, for tips on how to start a successful business. Here’s what she had to say:

- Write a detailed business plan. All aspects of your business should be included in your business plan. This document should outline your strategy for reaching customers, funding the business and managing employees, among other details. You can adjust your business plan at any point, so you may want to leave room for flexibility to adapt to changing circumstances.

- Clean up your credit. As a new business owner, your personal credit will play a role in whether you get approved for financing, such as a business loan or startup business loan. Lenders often look at a business’s sales history and financial statements when reviewing a loan application. However, until you’ve been in business for at least a year, you can expect a lender to heavily analyze your personal financial history instead.

- Aim to build brand loyalty. Think about the product or service you offer and whether your customers could make repeat purchases. To make sure your business has staying power, you’ll need to give customers a reason to return. Fostering a loyal customer base could be a key to success.

- Seek local funding opportunities. Many business loan and grant programs are available at the state or city level to help local business owners survive the pandemic. For instance, underserved business owners in Tennessee can apply for grants up to $30,000 to reimburse business interruption costs, while business owners in Charlotte, N.C., could receive grants up to $5,000 or $6,000 (dependent on location) for each local resident they hire. In many cases, business owners don’t need to repay grants. You may be able to qualify for assistance programs designed specifically for struggling entrepreneurs in your area. The Small Business Association has a tool to help you find local assistance.

Methodology

LendingTree researchers analyzed data from the U.S. Census Bureau Business Formation Statistics to compare business formation trends over time and by industry. Data covers the period from the first week of 2006 to the 43rd week of 2020, which ended Oct. 24.

Compare business loan offers