About Half of Cardholders Back a Credit Card Rate Cap, Even If It Means Reduced Access to Credit and Rewards

More than 8 in 10 American credit cardholders would support some version of a credit card interest rate cap similar to the one recently proposed by Sen. Bernie Sanders and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, according to a new report from LendingTree. However, the report showed major cracks in support for a cap when cardholders were asked about what could happen if a cap took effect.

When asked if they’d support a rate cap if it meant reduced access to credit for those with imperfect credit or if it meant less lucrative credit card rewards – two possible consequences of a rate cap, according to many in the financial services industry — about half of American cardholders said yes.

LendingTree surveyed more than 1,000 credit cardholders for their views on the May 2019 proposal from Sen. Sanders (D-VT), one of the leading contenders for the 2020 Democratic presidential nomination, and Rep. Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) to cap credit card interest rates at 15% nationwide. (Currently, there is no cap on bank credit card interest rates, though credit union card APRs are currently capped at 18% by law.) We also asked about other topics involving the regulation of credit cards, including several questions from a previous survey done this past December and January.

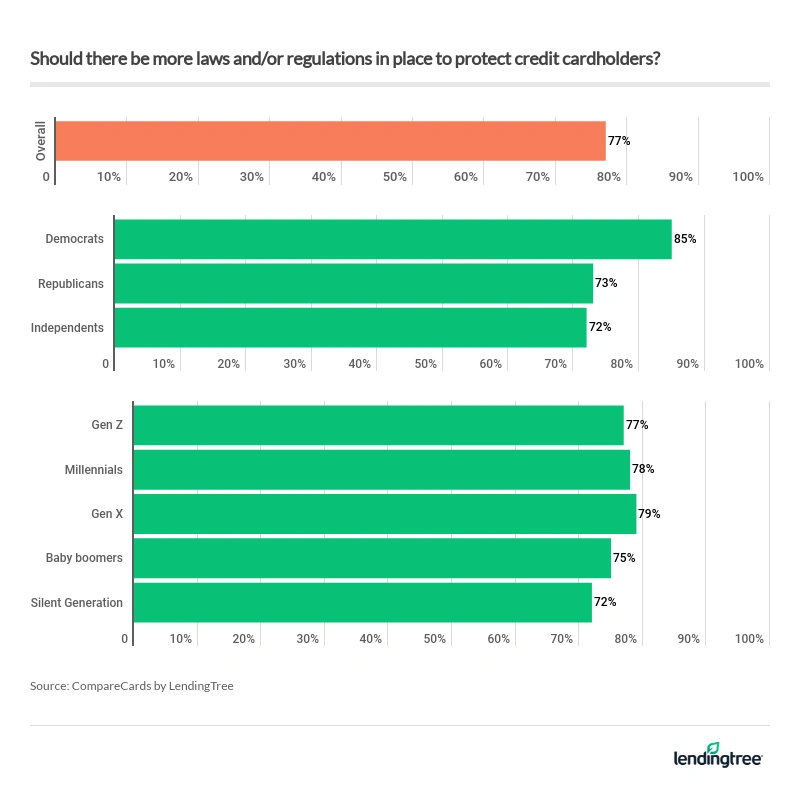

As we did six months ago, we found widespread, bipartisan support for greater regulation of credit cards. However, we also found that support for a rate cap fell sharply when questions got a little more detailed, including asking about potential consequences of the cap for the consumer.

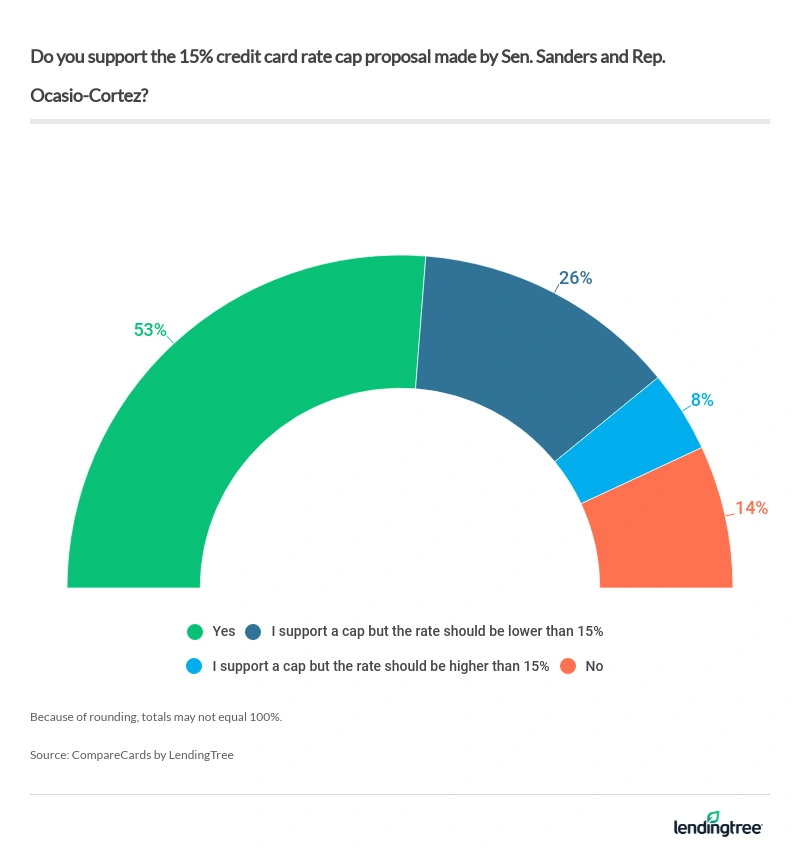

- About half of American cardholders (53%) said they support Sen. Sanders and Rep. Ocasio-Cortez’s proposal to cap rates at 15%. Another 26% said they support a cap but think the maximum rate should be lower than 15%, and another 8% support a cap, but think the maximum rate should be higher than 15%. In all, just 14% said they didn’t support any form of the proposal.

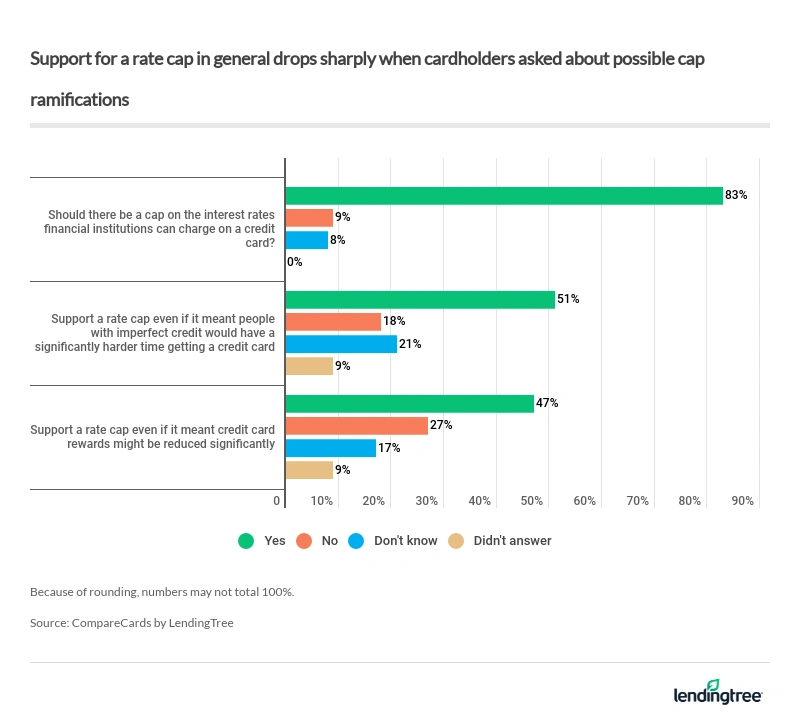

- When asked broadly about rate caps rather than about a specific proposal, 83% said they feel there should be a cap on the rates a financial institution can charge on a credit card.

- 51% of cardholders said they would support a rate cap if it meant people with imperfect credit would have a significantly harder time obtaining a credit card, while just 18% said no. (21% said they didn’t know; 9% didn’t answer.) Boomers were the most likely age group to agree.

- 47% of cardholders said they would support a rate cap if it meant credit card rewards might get reduced significantly, while just 27% said no. (17% said they didn’t know; 9% didn’t answer.)

- 77% of cardholders agree that there should be more laws and/or regulations in place to protect cardholders, while just 9% disagreed. (That’s down slightly from 79% in a previous survey.) 85% of Democrats agreed, as did 73% of Republicans.

A preview of things to come?

As popular as the general idea of a credit card rate cap might be with the public, there’s absolutely no chance of it becoming a reality under the current administration in Washington, D.C. The president and his team have been clear in their support of reducing regulations on business rather than ramping them up, and there’s no reason to expect that to change. However, if the Democrats win the White House and the Senate in 2020 – both of which are possibilities — things could change very quickly.

If that were to happen, it’s possible we’d see a push for additional regulation of the credit card industry, similar to what we saw when President Barack Obama took over in 2008. A year later, the Credit CARD Act of 2009 became law, bringing massive pro-consumer changes, including limiting when banks could raise a card’s interest rate, what disclosures were required and how payments are applied to balances, just to name a few. Of course, the economic situation of the nation is very different today than it was when President Obama took over, but the appetite for more oversight of financial products like credit cards is still strong for many Americans.

82% of credit cardholders say more laws, regulations needed to protect them; up from 2019

One of Sen. Sanders’ rivals for the Democratic nomination, Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass), has also introduced legislation to bring about a credit card rate cap. Sen. Warren and three other Democratic senators introduced The Empowering’ States’ Rights To Protect Consumers Act in April. Rather than instituting a federal rate cap, the Act seeks to amend current regulations to require lenders to adhere to the interest limits set by the state in which the customer lives.

Currently, banks only have to adhere to interest rate limits of the state in which the bank is based. For example, if your state caps rates at 18%, your credit card lender would have to do the same, regardless of the state in which the lender is based. (Ed. note: We did not ask about Sen. Warren’s proposal in our survey.)

Other 2020 Democratic presidential candidates have been largely silent on interest rate caps. LendingTree reached out multiple times to all the other 18 Democratic candidates who will participate in nationally televised debates in June for their comment on a rate cap. Fifteen failed to reply altogether, while three replied but either declined to comment or never provided comment.

APR caps would have massive potential ramifications

Currently, the average credit card rate is about 17 percent, and most new credit card offers come with a range of APRs anywhere from about 15% to 24% or higher. The idea of capping rates at a level below today’s current national average has great obvious appeal, but many in the financial industry paint a bleak picture of what the credit card landscape would look like under a rate cap.

They say millions of card accounts would be closed because banks would not be willing to extend credit to risky borrowers at that APR. Most card issuers engage in what’s called risk-based pricing, meaning less-risky borrowers pay lower APRs while riskier ones pay higher rates.

The reason being risky borrowers are far more likely to default, so banks charge higher rates as a hedge against possible loan losses. Without that flexibility, many think that banks would simply choose not to lend to those without good credit, leaving many to find other more expensive borrowing options.

They also say that credit card rewards would likely dry up, at least to some degree, because banks would no longer be able to afford to support them.

We saw something similar happen to debit card rewards when the Durbin Amendment of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform And Consumer Protection Act – passed as a reaction to the global economic crisis – capped the rates card companies could charge merchants for accepting debit cards. The cap in so-called interchange rates hit the banks’ bottom line hard, and debit card rewards became virtually extinct. (They have made a small comeback in recent years, but they’re still nowhere near as prominent as they had been.)

Both of these outcomes are clearly a big deal to cardholders, since support for a rate cap drops sharply when asked if reduced access to credit or reduced reward would come as a result. It also further drives home the importance of credit card rewards to cardholders, since they were more likely to reject a rate cap that would reduce rewards than one that would reduce credit access.

Could all of these things happen if a rate cap were to pass? Yes. To be frank, things would probably get a little crazy for a while as the banks figured out how to cope in a post-rate-cap world. We saw something similar happen after the CARD Act of 2009.

For example, credit card interest rates went sky-high for a short time as banks figured out how to recoup revenue lost with the new regulations without alienating consumers. (One credit card even famously charged a 79% interest rate for a short time.)

Under a rate cap, banks’ efforts to bring back revenue would look quite different: For example, fees would almost certainly increase and 0% balance transfer offers could vanish. Other card issuers could simply shut down lending to certain groups of borrowers altogether, at least for a while.

Add it all up, and banks have billions of reasons to not want this to happen. But that doesn’t mean it won’t.

The bottom line: Don’t expect calls for a rate cap to fade

In today’s hyper-polarized political landscape, a credit card rate cap is a rare example of something that most Americans agree on regardless of their political preference, at least in theory. Yes, that support takes a big hit when people find that it could hinder credit access or reduce rewards. However, when you exclude the people who answered “I don’t know,” you still find far more people supporting the idea of a rate cap rather than opposing it. And when something is that popular, it becomes very hard to ignore.

Again, any rate cap proposal is dead in the water, legislatively, until at least the 2020 elections are over, and if President Trump wins a second term and/or the Republicans maintain control over at least the Senate, it will likely remain that way for many more years. However, both of those are far from certain. Ultimately, consumers certainly shouldn’t hold their breath for a rate cap to come about, but banks would be wise not to simply laugh it off or dismiss it out of hand either.

Methodology

LendingTree commissioned Qualtrics to conduct an online survey of 1,046 American credit cardholders, with the sample base proportioned to represent the general population. The survey was fielded June 10-11, 2019, and the margin for error for all respondents is +/- 3%.