82% of Credit Cardholders Say More Laws, Regulations Needed to Protect Them; Up from 2019

A growing percentage of credit cardholders — including large majorities among Republicans, Democrats and independents alike — say the government needs to do more to protect them, according to a new LendingTree survey.

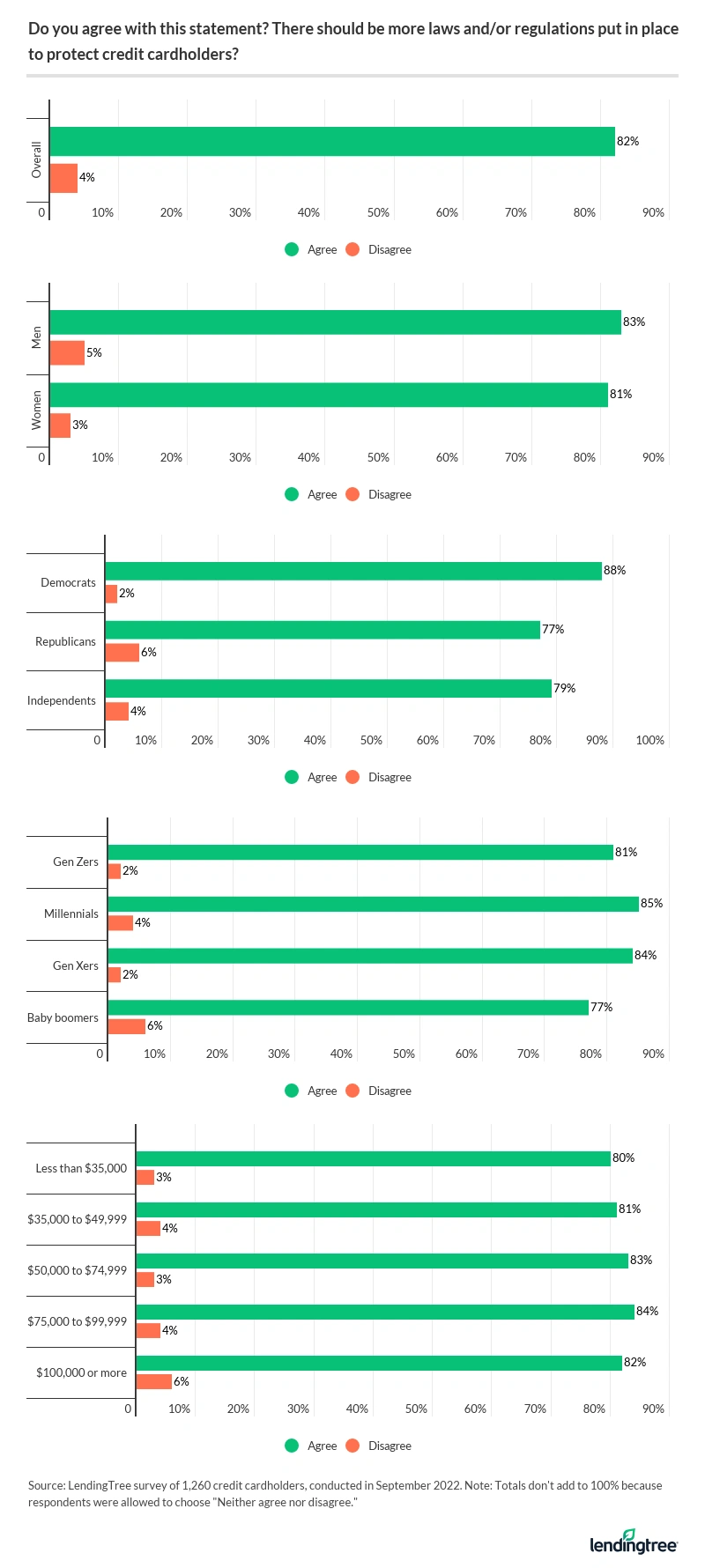

More than 8 in 10 (82%) credit cardholders at least somewhat agree there should be more laws and regulations to protect them. That’s a 5-point increase from 2019, the last time we surveyed cardholders on the topic.

The survey also shows widespread approval for a credit card rate cap, a maximum interest rate that issuers could charge. There’s a cap on the interest rates that can be charged on credit cards issued by federal credit unions, but there’s no maximum rate on other types of credit cards. However, the survey shows clear support for a rate cap, even if it means reducing rewards or access to credit.

To be clear, there’s virtually no chance of a rate cap anytime soon, despite this survey of 1,260 credit cardholders showing it’s something that most Americans support. However, other credit card regulations may be on the way, as the White House announced in late September its intent to crack down on “junk fees” across many industries, including credit card late fees.

- Support for additional credit card regulation is growing. 82% of credit cardholders agree there should be more laws or regulations to protect them, a 5-point increase from June 2019.

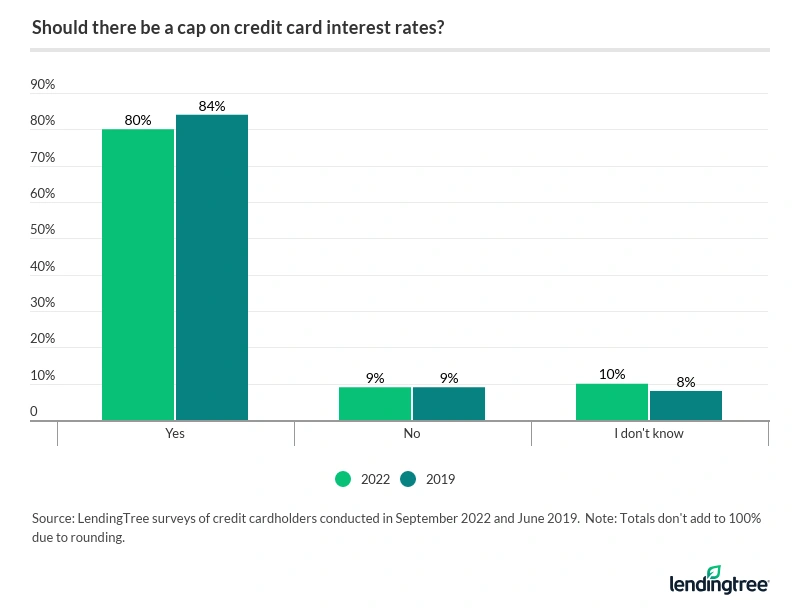

- Support for a credit card rate cap dips slightly but is still widespread. 80% of cardholders say they approve of capping the rates charged on a credit card. That’s down 4 points from June 2019, though the percentage of those opposing the cap remains unchanged at 9%.

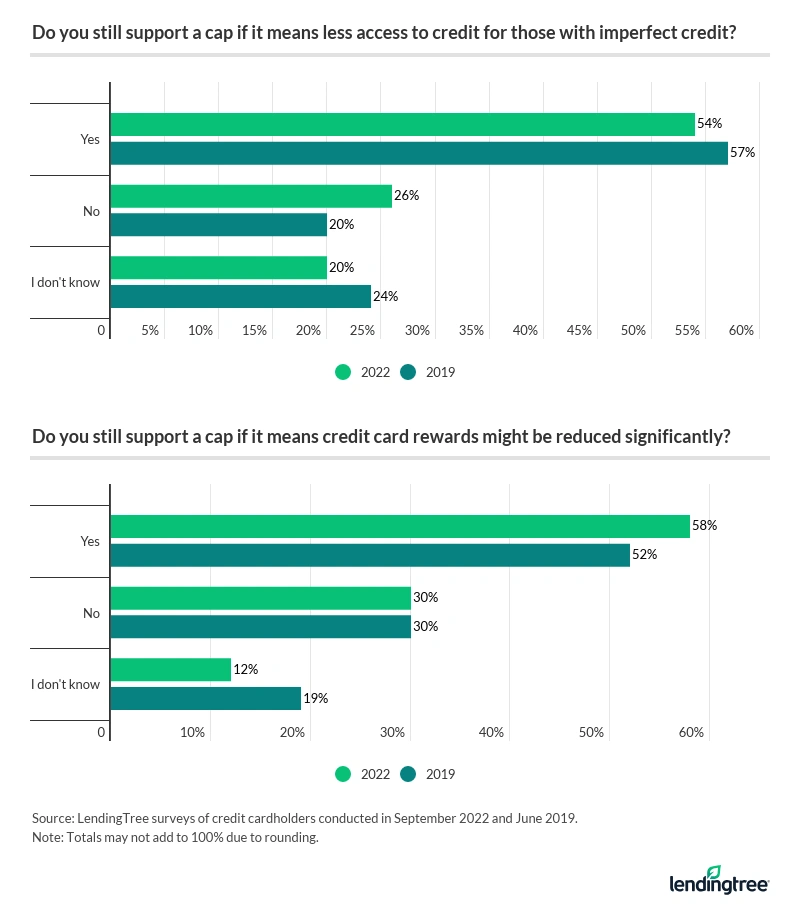

- More cardholders are still willing to back a credit card rate cap even if it means less lucrative rewards. 58% of those supporting a rate cap say they’d still back it even if it meant credit card rewards might be reduced significantly. That’s up from 52% in June 2019.

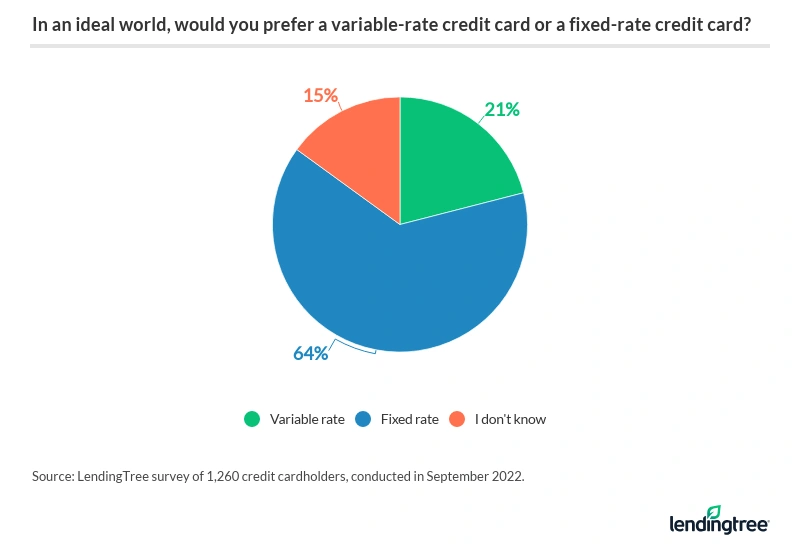

- Nearly 2 in 3 cardholders prefer a fixed-rate credit card to one with variable rates. The vast majority of credit cards in America come with variable rates and move when the Fed changes rates. 64% of cardholders say they’d prefer a card that was fixed, while just 21% prefer variable-rate cards. (15% say they don’t know.)

Support for additional credit card regulation is growing

In today’s hyperpolarized America, there are very few things that we as a country seem to agree on. One of them, however, appears to be the need for more credit card regulation.

We asked whether cardholders agreed with the following statement: “There should be more laws and/or regulations in place to protect credit cardholders.”

No matter the gender, age, income level or political party affiliation, a significant majority of Americans say they agree.

Older, lower-income Americans are the least likely to agree — but even in those groups, the support is still widespread. Just 77% of baby boomers ages 57 to 76 agree, versus 85% of millennials ages 26 to 41. Meanwhile, 80% of those making $35,000 or less support more laws or regulations, compared with 84% of those making between $75,000 and $99,999 and 82% of those making $100,000 or more.

Perhaps not surprisingly, Democrats are the most likely to favor increased regulation, with 88% saying so. However, independents (79%) and Republicans (77%) are also heavily likely to support it.

Just 4% of cardholders say they disagree, while 14% say they neither agree nor disagree. That means Americans are more than 20 times more likely to agree with the statement than to disagree.

Support for a credit card rate cap dips slightly but is still widespread

Cardholders are also united in their support of a credit card rate cap. Eight in 10 cardholders say there should be a maximum interest rate that issuers can charge credit cardholders, while just 9% disagree and 10% don’t know.

Today, there is a rate cap on credit cards issued by federal credit unions — they can’t charge more than 18% — but there isn’t one for other types of cards. Thanks to the landmark Credit Card Accountability Responsibility and Disclosure (CARD) Act of 2009, there are restrictions on when card issuers can raise cardholders’ interest rates, but that legislation didn’t include implementing a maximum interest rate for credit cards.

In 2019, U.S. Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) and U.S. Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.) proposed legislation that capped credit card interest rates at 15%. Ultimately, nothing came of it — as has been the case with other such proposals — but the legislation was popular with cardholders. In the 2019 LendingTree survey mentioned earlier, 53% of cardholders said they supported the proposal, while another 26% said they supported rate caps but thought the cap should be lower than 15%. Just 14% opposed it.

Cardholders today express support in large numbers when asked about rate caps in general instead of specific legislation. However, overall support for a rate cap dipped slightly — from 84% in 2019 to 80% today — while those opposed remained unchanged at 9%. That may be surprising, given that credit card interest rates are higher today than in 2019, but support remains high.

Virtually all those who support a rate cap (97%) say the cap should be 20% or lower, including 44% who say it should be 10% or lower.

Rate cap remains popular even if it means fewer rewards

It’s easy to see why a rate cap is popular. No one likes paying interest. However, implementing a rate cap would likely have a profound impact on the industry and credit cardholders alike beyond reducing interest payments.

Most important, it would likely lead to reduced access to credit for those with imperfect credit. Banks charge interest to reduce risk if cardholders don’t pay what they owe. The greater the risk, the higher the interest rate charged. That’s why folks with low credit scores are typically charged the highest interest rates, sometimes 25% or higher. If banks could no longer charge the interest rate they choose, many would choose to no longer lend to riskier borrowers, leaving those folks to pricier options like payday loans.

A rate cap would also likely lead to fewer and less lucrative reward offerings because banks would feel they could no longer afford them. We saw something similar in 2010 when the Durbin amendment — part of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act that was passed during the Great Recession — substantially reduced the amount of fees card companies could charge merchants for accepting debit cards. Those fees often helped fund debit card rewards, and once the fees shrunk, debit card rewards largely vanished. A rate cap could lead to a similar shake-up in the credit card space.

When asked to consider these two scenarios, support for a rate cap falls significantly, though cardholders are still about two times more likely to support a cap than to oppose one.

Compared to 2019, we saw a significant increase in the percentage of cardholders who backed a rate cap if it meant losing rewards and a slight decrease in those supporting it if it meant reduced credit access.

Fixed-rate credit cards would be a popular option

The vast majority of credit cards in America today are variable-rate cards. For most of those cards, that means when the Federal Reserve raises or lowers rates, the rates on those cards will go up or down by the same amount, usually within a billing cycle or two. And unlike most other fee and rate changes to your credit card, the issuer doesn’t have to give you advance notice that your rate will change. They just do it. Americans have likely learned that the hard way several times in 2022, as the Fed has raised rates five times this year alone.

Variable-rate cards didn’t always dominate the credit card landscape this way. So-called fixed-rate cards — which aren’t tied to Fed rate moves — were once far more common. However, the Credit CARD Act of 2009 clamped down on issuers’ ability to raise rates on credit cardholders, prompting more issuers shortly after to introduce more variable-rate credit cards.

Fixed-rate cards do exist, though they’re rare. Many of the few that exist are marketed toward those with thin or imperfect credit and feature higher-than-average APRs. However, our survey shows that cardholders wish fixed-rate cards were less rare.

Respondents are three times more likely to prefer a fixed-rate card over a variable-rate card (64% to 21%). Men and women are nearly equally likely to prefer a fixed-rate card (64% and 65%, respectively). But the preference for a fixed-rate card rises with age, with 72% of baby boomers saying they’d choose that option, versus just 53% of Gen Zers ages 18 to 25.

That preference shouldn’t be surprising, given how quickly interest rates have risen in recent months. However, fixed-rate cards aren’t without major issues. Here are two important things to remember about fixed-rate credit cards:

- Your rate can still change for various reasons, including being 60 or more days late with a payment. Issuers just have to give you at least 45 days’ written notice before they do so.

- When the Fed eventually begins to lower rates in the future, your fixed-rate card’s APR won’t decrease with it. You’d be locked in at that higher rate unless you negotiate a lower rate with the issuer or change to another card with a lower rate.

Despite the public’s apparent appetite for these cards, don’t expect a torrent of fixed-rate cards to hit the market soon. While we may see more of them as rates continue to rise, fixed-rate cards will almost certainly remain the exception rather than the rule for the foreseeable future.

The bottom line: Some changes may be ahead, but not a rate cap

It’s rare for 80% of Americans to agree on much of anything these days. However, credit cardholders are united in their support of extra regulation of the credit card business, and that appears to be what is coming from the White House in the near future.

In June, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) announced it was gathering information from credit card issuers, consumer groups and the public ahead of proposing new rules governing credit card late fees.

Then, on Sept. 26, President Joe Biden said the White House Competition Council was working on a plan to reduce or eliminate so-called junk fees. In his speech at the council meeting, he specifically mentioned targeting checking account overdraft fees, cellphone plan termination fees and credit card late fees.

Details of these plans are still to be announced. However, what is clear is that there’s no rate cap coming to rescue cardholders from rising interest rates. That means that your best move is to take your own steps to combat rising interest rates.

- Pay down your credit card debt: That debt will only get more expensive if you don’t do anything about it. It’s easier said than done, but finding extra funds to knock down that credit card debt is more important now than ever.

- Consider 0% balance transfer cards and low-interest personal loans: These are some of your best weapons in the battle against credit card debt. A balance transfer credit card in particular can give you up to 21 months interest-free on transferred balances, potentially saving you a significant amount of money. Despite rising interest rates, these cards are still widely available, though you’ll likely need good credit to get one. If you don’t qualify, a low-interest personal loan could be a good option, as well.

- Ask for help: Seven in 10 cardholders who asked for a lower APR in the past year got one, but far too few people ask. There’s no guarantee you’ll get your way, but with high success rates, it’s not just those with 800 credit scores seeing rates lowered.

- Build your emergency fund: The best way to avoid rising interest rates is to not grow your debt in the first place. That’s a whole lot easier when you have savings. If you pay off your credit card debt but don’t have savings, your next unexpected expense will just go on to your credit card, keeping the cycle of debt spinning indefinitely. Again, it’s easier said than done, but stashing away money while paying down debt will pay dividends in the long run.

Methodology

LendingTree commissioned Qualtrics to conduct an online survey of 1,577 U.S. consumers — 1,260 of whom are credit cardholders — ages 18 to 76 from Sept. 23 to 24, 2022. The survey was administered using a nonprobability-based sample, and quotas were used to ensure the sample base represented the overall population. All responses were reviewed by researchers for quality control.

We defined generations as the following ages in 2022:

- Generation Z: 18 to 25

- Millennial: 26 to 41

- Generation X: 42 to 56

- Baby boomer: 57 to 76