10 Years After The Credit CARD Act, 8 In 10 Americans Still Want More To Be Done

Ten years after a landmark federal law transformed the credit card industry, a large majority of Americans say they still want more to be done to protect consumers.

LendingTree surveyed more than 1,000 Americans to find out their views on the Credit Card Accountability, Responsibility and Disclosure Act of 2009 – better known as the Credit CARD Act – a decade after President Barack Obama signed it into law on May 22, 2009. The Act, among other things, limited banks’ ability to increase interest rates on existing credit card balances, required people under 21 to have an adult co-signer or show proof of income in order to get a card, restricted banks’ ability to charge overdraft fees, ramped up disclosure requirements and mandated that any payments above the minimum be applied to higher interest balances first. In short, it was a very big deal for consumers.

It didn’t change everything, though. For example, it did not cap how high the standard purchase interest rate could be on a credit card.

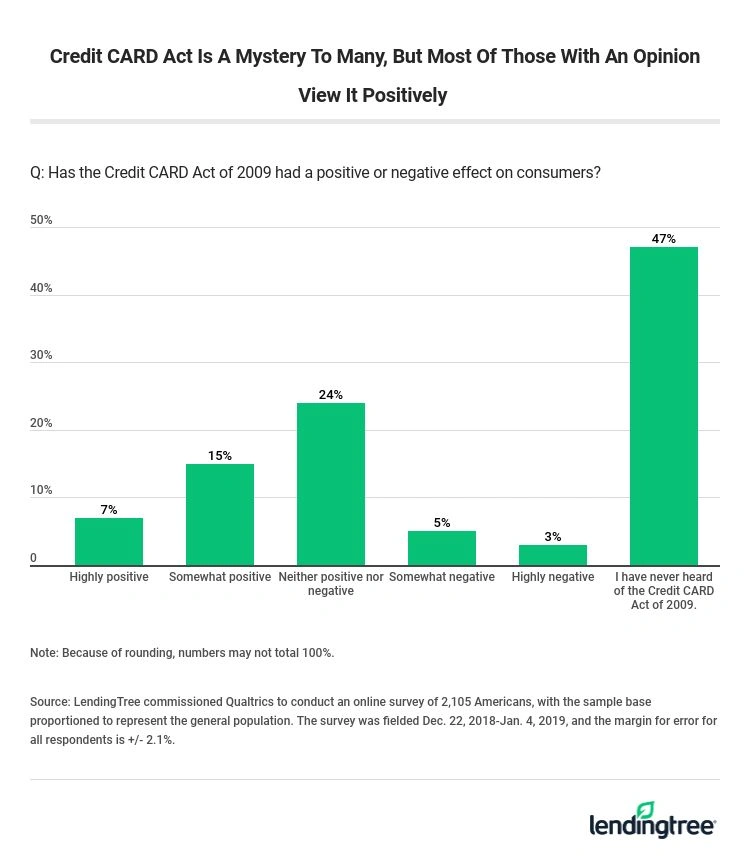

With the 10th anniversary of the CARD Act upon us, LendingTree wanted to see what people thought of these changes. What we found was that nearly half of Americans had never heard of the CARD Act, but among those who had, nearly three times as many viewed it as a positive as saw it as a negative.

But even if Americans hadn’t heard of the Act, they wanted more to be done to protect cardholders. The vast majority want even more laws to protect consumers, including a limit on just how high credit card interest rates can go.

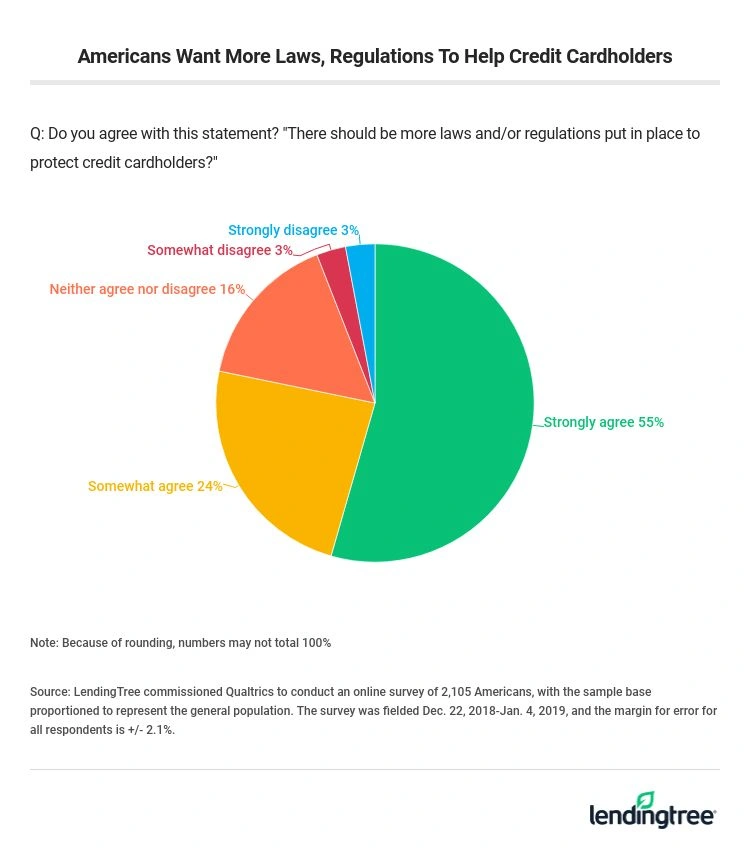

- 79% of people agreed there should be more laws and/or regulations put in place to protect credit cardholders, while just 6% disagreed. (Even 77% of Republicans agreed.)

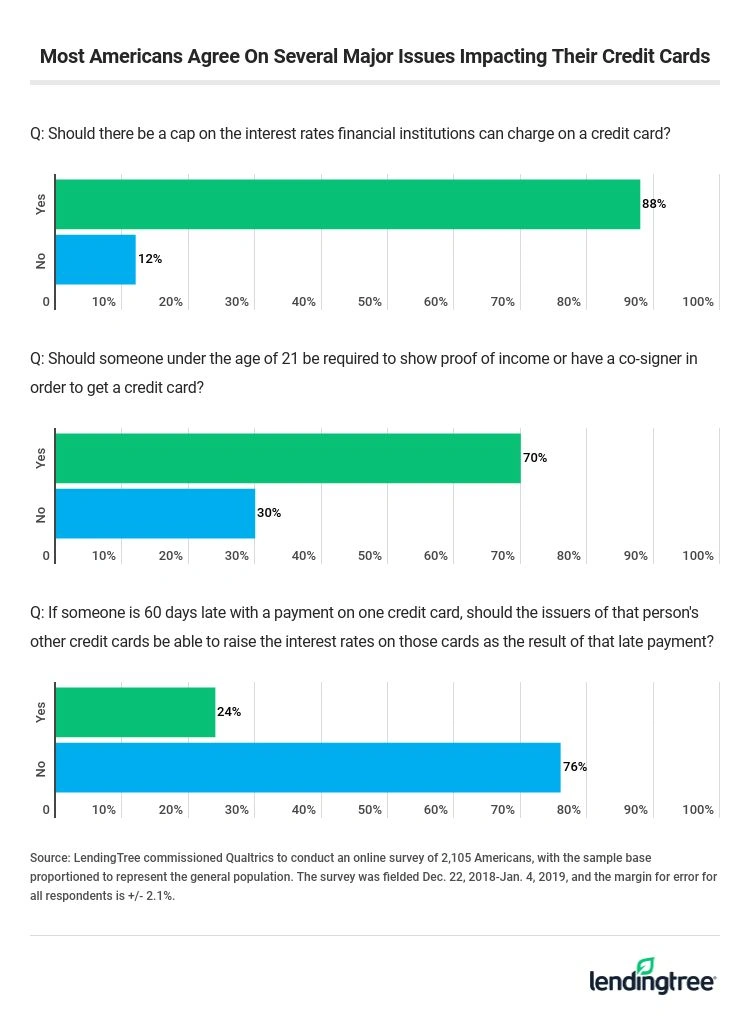

- 88% said there should be a cap on the interest rates financial institutions can charge on a credit card. Those with the lowest incomes are least likely to support a cap, while those with the highest incomes are most likely to support.

- Nearly half of Americans (47%) when asked whether the Credit CARD Act of 2009 had a positive or negative effect on consumers said they had never heard of the CARD Act. Of those who were aware of it, 40% said it had a positive effect, while just 15% said it was a negative and 45% said neither.

- 70% said someone under the age of 21 be required to show proof of income or have a co-signer in order to get a credit card – and the older you are, the more likely you are to agree.

- Nearly 1 in 4 (24%) said if someone is 60 days late with a payment on one credit card, the issuers of that person’s other credit cards should be able to raise the interest rates on those cards as the result of that late payment. (That’s describing the much-reviled policy of universal default, which the CARD Act basically did away with)

Bottom line: There’s more work to be done protecting cardholders

There’s no ambiguity here: despite the success of the CARD Act, American credit cardholders want more credit card protections.

The passage of the Credit CARD Act was an earthquake in the world of credit cards, but 80 percent of Americans say more still needs to be done. What they want more than anything – and understandably so – is a cap on just how high credit card interest rates can go.

Federal law restricts credit unions from charging higher than an 18 percent APR on a credit card, however no such restriction exists for other financial institutions. Generally, the highest APR you’ll see for a credit card today is around 30 percent, but non-credit-union issuers are free to go as high as they see fit, and for a while after the Credit CARD Act’s passage, they did just that. Struggling to determine where they would make up for lost interest and fee revenue caused by the act’s restrictions, banks experimented with rates, including one issuer that briefly charged a mindboggling 79.9% APR. Banks eventually found their footing in the post-CARD Act world, leading to a period of unusual rate stability for several years until the recent spate of increases from the Federal Reserve sent variable-rate APRs to record levels.

Given all that and the $1 trillion-plus credit card debt facing Americans today, it shouldn’t be surprising that 90 percent of consumers said they want a cap limiting how high credit card interest rates can go. Even if that cap was 20% or 22% rather than the 18% cap used by credit unions, that rate reduction would mean major savings for folks with credit card debt.

Now don’t kid yourself: A cap on credit card rates won’t come anytime soon. Lots of people and businesses have billions of reasons why they’d fight to the bitter end to allow a cap on APRs from happening. And if it did happen, know that financial institutions would find other ways to make up for any lost revenue – through fee increases and other means. However, that doesn’t mean that a rate cap can’t happen and that it isn’t a battle worth fighting.

The recent government shutdown gave us a glimpse at how many Americans are teetering on the edge financially. They’re just one or two missed paychecks or one medical emergency away from being in real financial trouble. They need all the help they can get to make ends meet.

Would a lower APR on their credit cards make a difference? Sure. Would it be a game-changer? Maybe not. However, millions of Americans would love the chance to see if it would.

Meanwhile, your best move today is to commit to making 2019 the year that you focus on paying down any credit card debt you’re carrying. The longer you put it off, the more expensive it’ll be and the longer it’ll take to pay down. That means that most cardholders can’t afford to wait any longer.

Methodology

LendingTree commissioned Qualtrics to conduct an online survey of 2,105 Americans, with the sample base proportioned to represent the general population. The survey was fielded Dec. 22, 2018-Jan. 4, 2019, and the margin for error for all respondents is +/- 2.1%.