47% of Unpaid Interns Take On Debt to Make Ends Meet

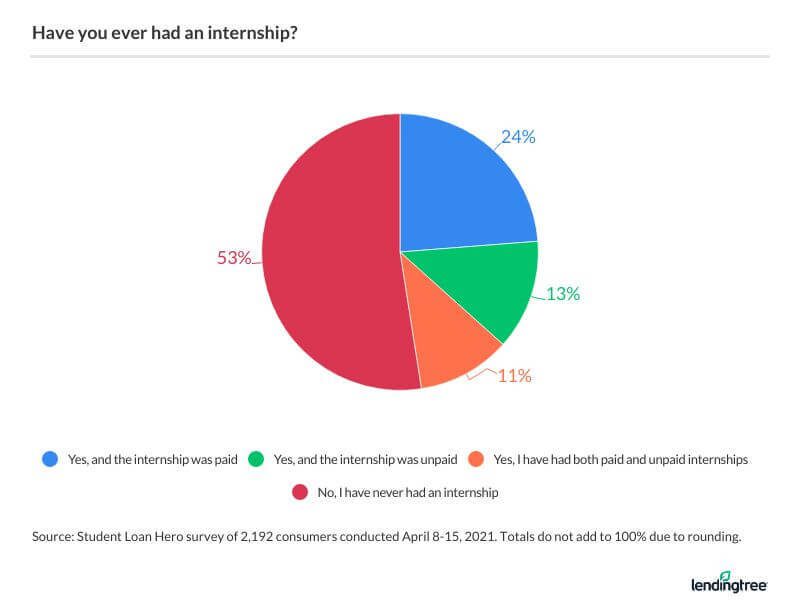

About a quarter of Americans have worked an unpaid internship, including almost 40% of Gen Zers and 30% of millennials, a new LendingTree survey finds. But some also say it’s unfair for employers to ask for free labor, when not everyone can realistically earn work experience in this way.

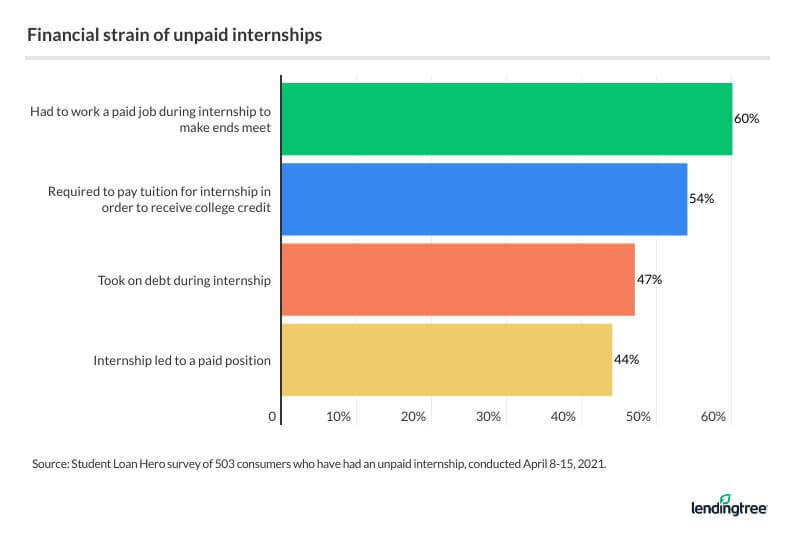

The problem is that students from less-advantaged backgrounds often face a significant financial strain from accepting such positions. Nearly half of former unpaid interns among the survey’s 2,100-plus respondents said they were forced to go into debt to manage expenses. Others took on a second (paid) job to make ends meet.

Yet despite the apparent inequality for students with lower incomes — as well as uneven outcomes depending on gender and race — the unpaid internship doesn’t appear to be going away anytime soon.

Key findings

- Given the lack of wages, 47% of unpaid interns reported taking on debt to complete their internship, with those debts averaging more than $2,500.

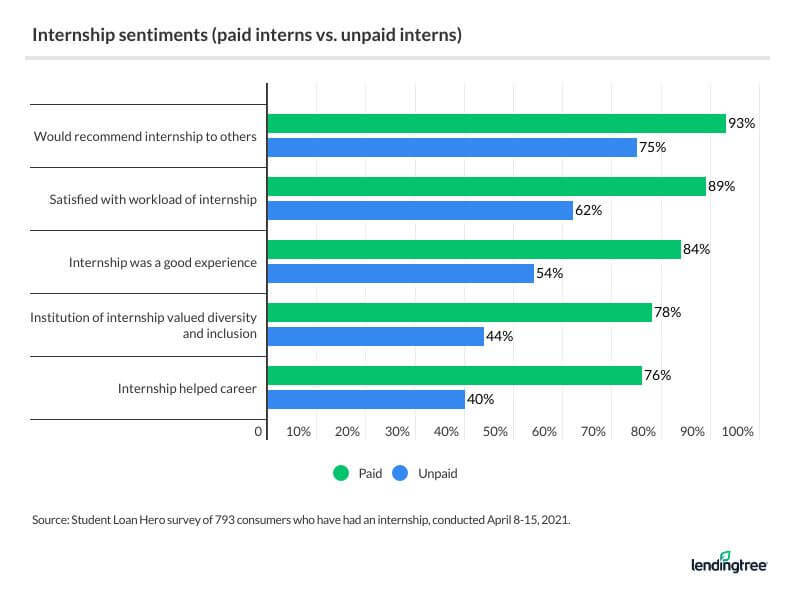

- While a solid majority (84%) of paid interns said the experience was a good one, a slimmer 54% of unpaid interns said the same.

- The survey found racial and gender disparities: A higher proportion of unpaid Black and Latino interns (57% and 58%, respectively) took on debt than did their white peers (39%), while 54% of male unpaid interns later accepted a paid role with the same employer, versus 37% of female interns.

- With unpaid internships being an unrealistic option for many, 54% of Americans agreed that they unfairly give wealthy students a leg up in career advancement. And yet, those who previously worked an unpaid internship were less likely to say they should be abolished.

Unpaid internships require some students to borrow, work a second job

For college students, an unpaid internship can be a stressful addition to their existing course load. According to our survey, it can also cause significant strain on their finances.

Students who were perhaps already relying on education loans to cover tuition found they needed to take on even more debt to cover other necessities while they punched the clock without pay.

The 47% of respondents who took on initial or additional debt to complete an internship borrowed an average of $2,500.

Why go to such lengths for work that doesn’t pay? Some respondents had no choice, with 67% of former unpaid workers reporting their internship was a graduation requirement.

Others might have viewed their internship, unpaid or not, as a valuable experience to add to a slim resume. Their expenses to receive that value included, in some cases, transportation: 41% of unpaid interns relocated for an internship in a town away from their home or school.

While some internships offer stipends to cover expenses such as transportation and equipment, that’s far from the norm. More than half (53%) of unpaid interns didn’t have any of their costs covered by their employer.

Internship outcomes show racial, gender gaps

As with many economic issues facing Americans, results were influenced by the race and gender of the intern, the survey found.

Across racial lines, 58% of unpaid interns who identify as Latino and 57% who identify as Black had to take on debt to get by, compared with 39% of white respondents.

Meanwhile, gender appeared to impact whether the unpaid internship led to a paying staff position. About 54% of men who worked an unpaid internship eventually took on a wage-earning role with the same employer, compared to 37% of women.

At the same time, 60% of men said their unpaid internship included some form of stipend for expenses, while only 35% of women received this important benefit.

Unpaid interns generally less satisfied by their experience

Because some employers and hiring managers may not put as much effort into managing unpaid interns as they would those who were paid, it’s not altogether surprising that just 62% of former unpaid interns were happy with their workload: 28% said they didn’t have enough to do, while 10% had too much work.

On the flip side, 89% of paid interns said they had the right amount of work. In fact, interns who received a paycheck reported being happier in many other important respects.

Overall, 84% of paid interns said they had a good experience in the workplace. Among their unpaid peers? Just 54%.

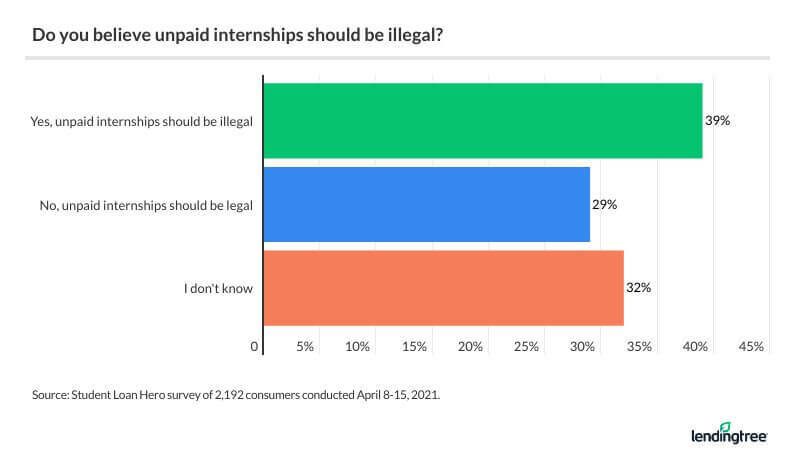

Americans question the fairness, legality of unpaid internships

With no pay — and perhaps not even stipends — unpaid internships are more realistic career-building experiences for students who don’t have to worry about money. However, students from lower-income backgrounds might find it extremely challenging to keep afloat with an unpaid internship.

This inequality left a slight majority of our survey respondents (54%) agreeing that unpaid internships disproportionately help better-off students gain crucial early job experience.

But surprisingly, veterans of unpaid internships were actually more likely to defend the practice of “free work.”

Just 35% of those who had been an unpaid intern said such internships should be made illegal, with a much larger 68% of former paid interns saying the same.

That said, it’s not unheard of for those who’ve suffered for a goal to see it as valid or even as a rite of passage.

Should you (or your child) take on an unpaid internship?

It’s unlikely unpaid internships will disappear anytime soon. Their popularity may even be gaining steam: As mentioned at the outset, nearly 40% of Gen Z and 30% of millennials have worked an internship without wages, compared to less than 10% of baby boomers.

If you (or your child) is attending college or will do so soon, you might be wondering whether to accept an unpaid position. Consider these questions first:

- Are there similar opportunities that come with pay (or at least a stipend)?

- If not, do the benefits — college credit, career experience, etc. — outweigh the costs?

- Could you live at home or work remotely to cut down on the expenses?

- Do you have enough savings or cash-flow to manage working for free?

- Would you have time to take on a second, paid position?

Your answers to these questions should help you determine whether or not to avoid unpaid internships. Checking in with your school’s career services department might also be helpful.

And don’t forget that these job opportunities aren’t all that unique. Evaluate work-study programs and part-time jobs or even on-campus apprenticeships. They could provide equally important experiences while also contributing to your bottom line.

Methodology

LendingTree commissioned Qualtrics to field an online survey of 2,192 Americans, which was conducted April 8-15, 2021. The survey was administered using a non-probability-based sample, and quotas were used to ensure the sample base represented the overall population. All responses were reviewed by researchers for quality control.

We defined generations as the following ages in 2021:

- Generation Z: 18 to 24

- Millennial: 25 to 40

- Generation X: 41 to 55

- Baby boomer: 56 to 75

While the survey also included consumers from the silent generation (defined as those 76 and older), the sample size was too small to include findings related to that group in the generational breakdowns.